The sun paints the room this morning. Spreading a yellow sheen over objects and things that are familiar, generating a glow of optimism which I feel as I stretch and shake away the sleep. I look around as I take out the bin and reflect on changes I want to make to myself.

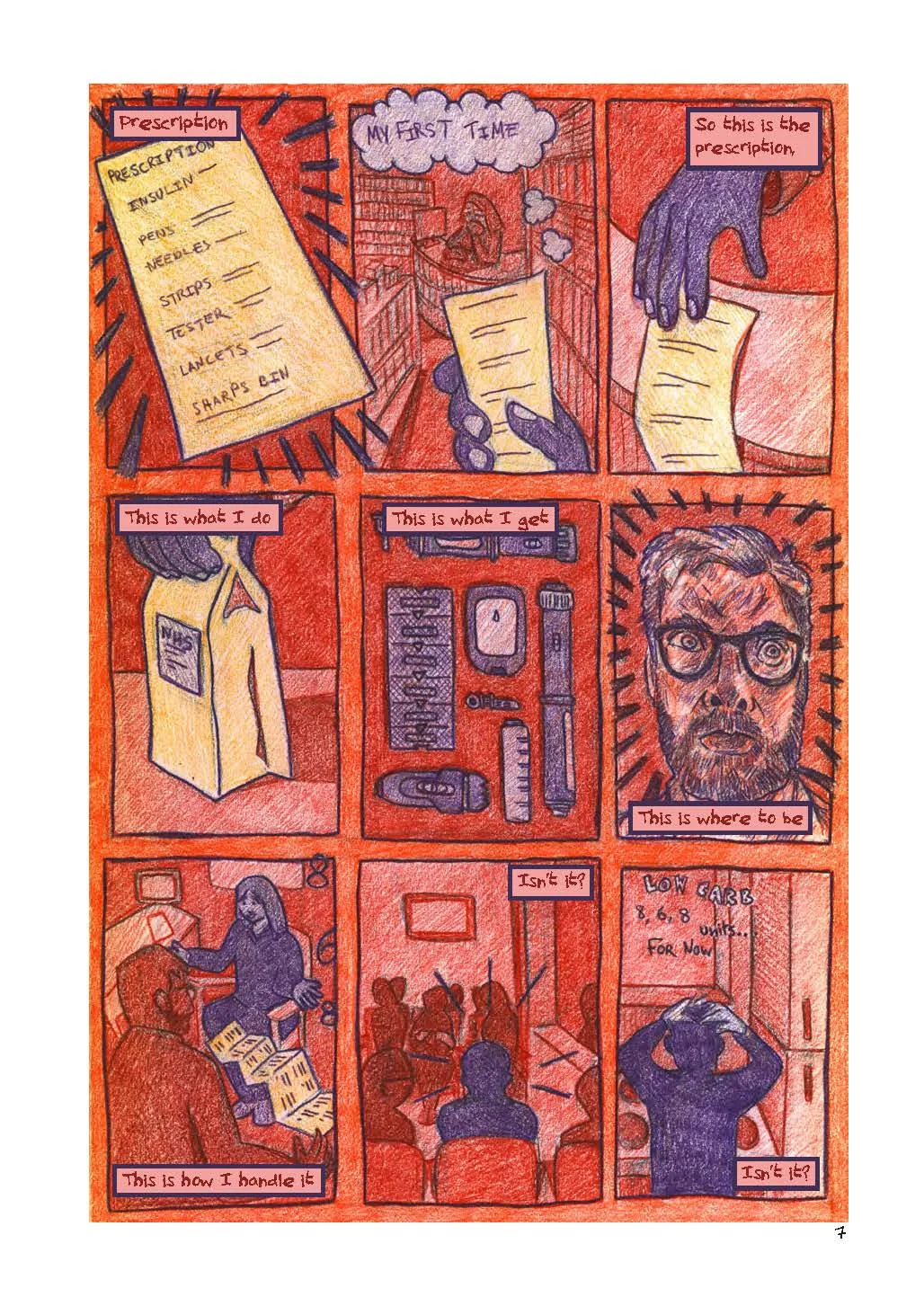

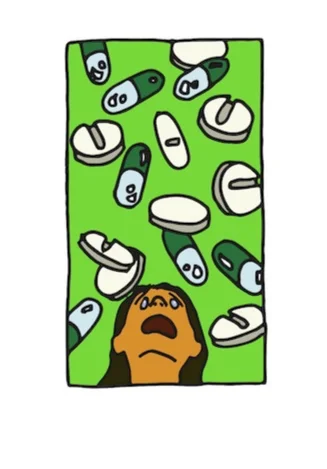

I bought running stuff yesterday – tops, shorts, trainers, and importantly a utility belt. I had a brief period way back before diagnosis where I did some exercise – some yoga, enough running to get me round the great north run (in no sort of time, but I didn’t die, so target achieved), but I’ve always felt self-conscious doing ANY form of exercise, I feel a fraud at best, and a fool more often. Type 1 Diabetes brings another element however, I need to do exercise to keep on top of my health, but I am really scared about having a hypo running by myself – will I recognise it whilst I’m sweaty and out of breath, will I react quick enough, will I be able to get around okay? This is where the Batman belt comes in – carrying my tester, strips, and sugar. I have a plan – including eating before I start (no insulin – I don’t want to store stuff, I need to use it), slow, short test runs with lots of test included to get a sense of the impact on my metabolism. This will be a new chapter for me, but my relationship with my body has been complex from the beginning.

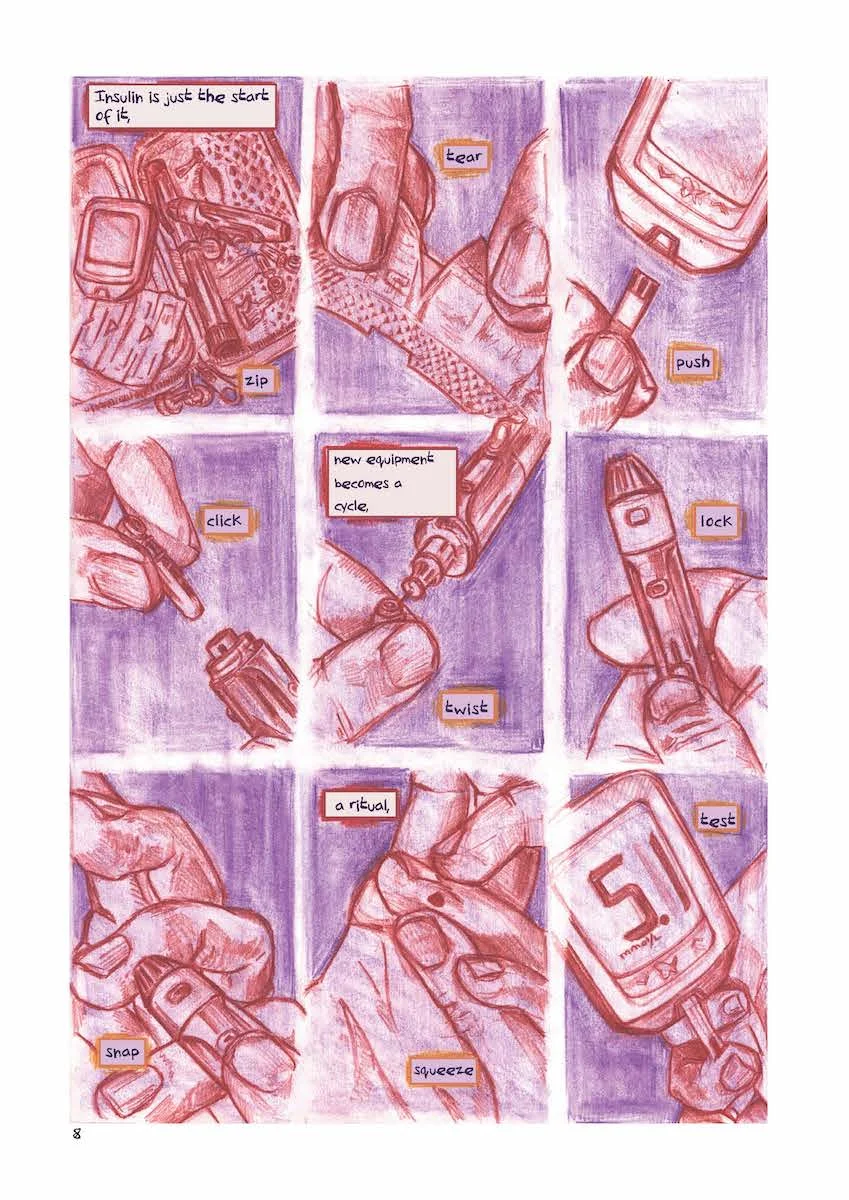

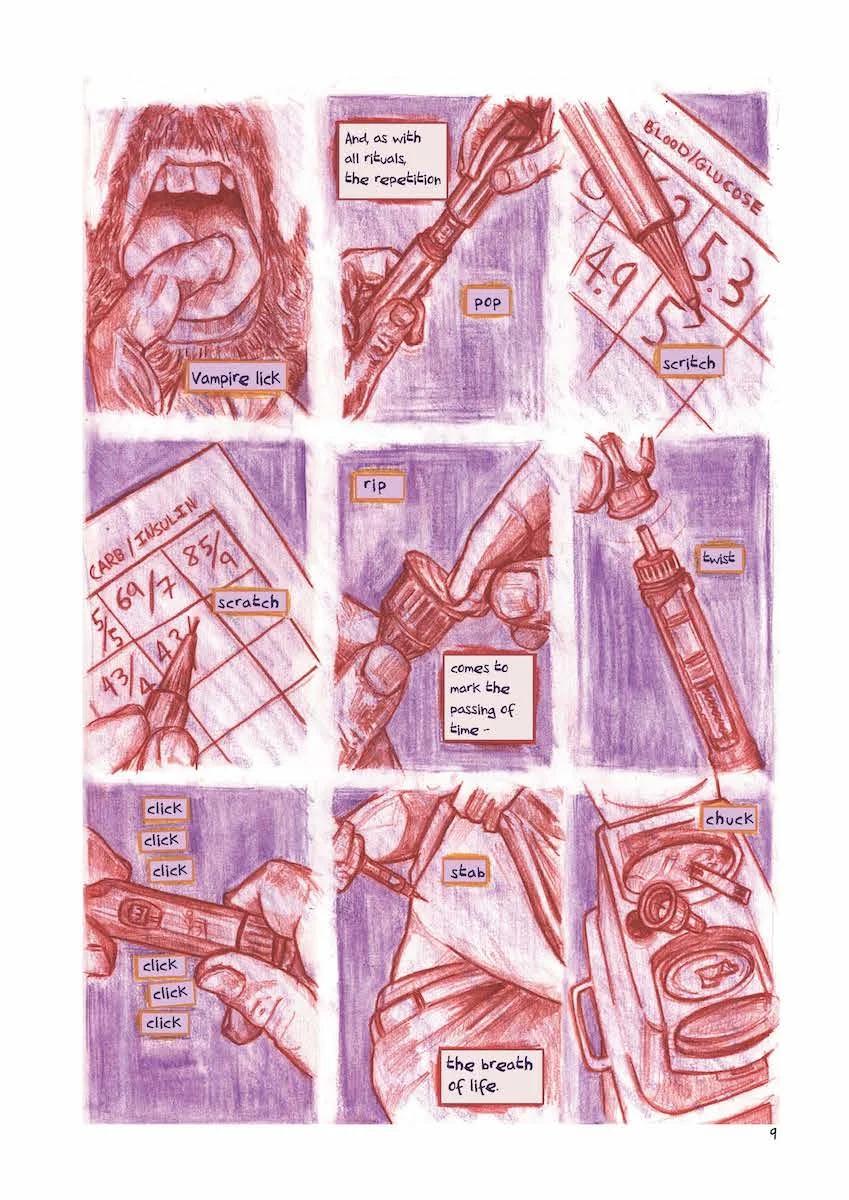

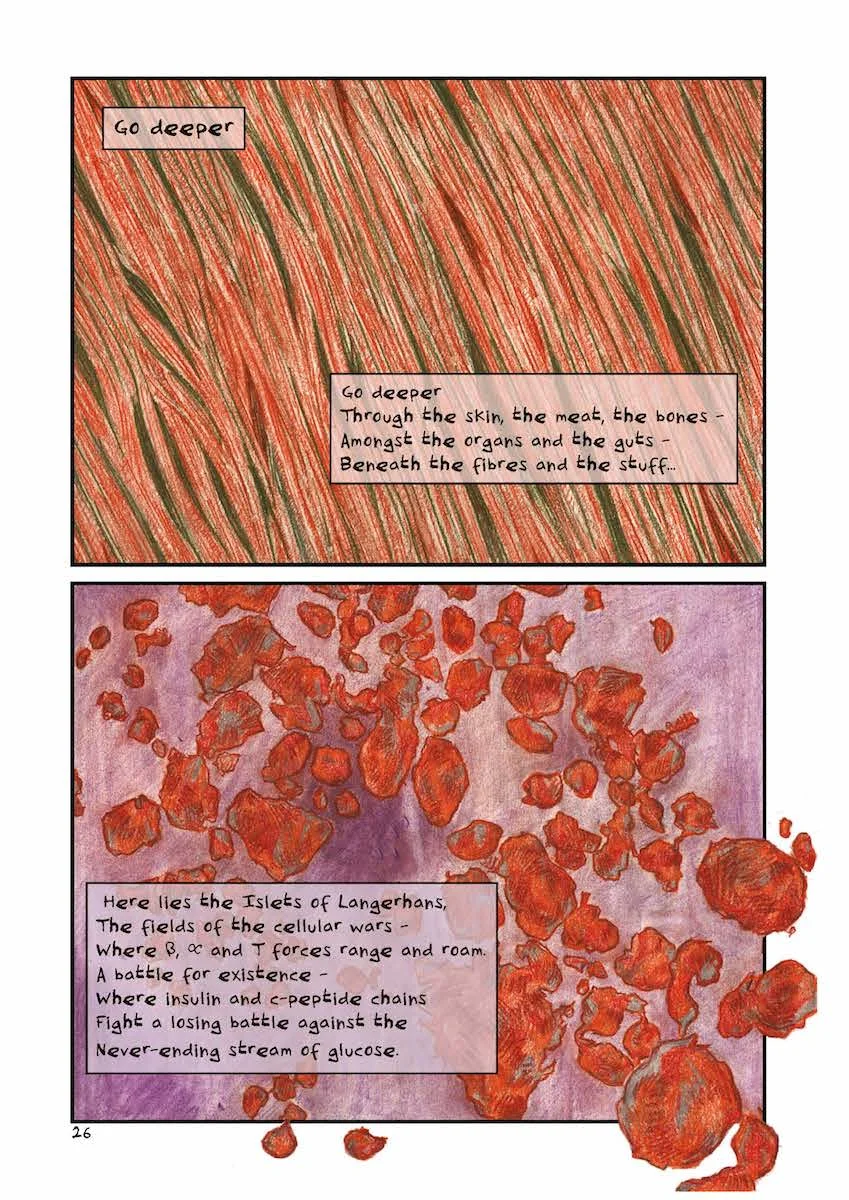

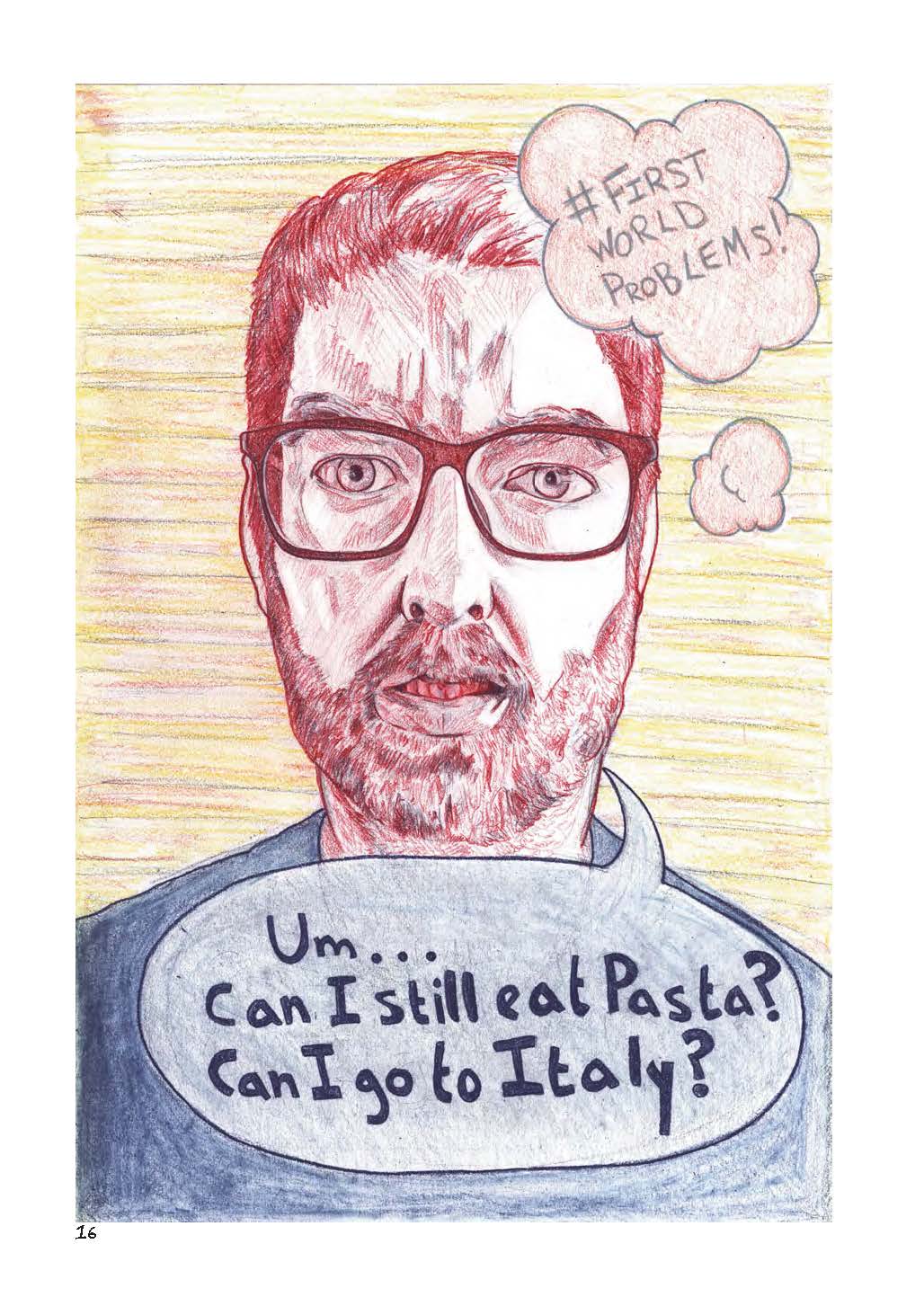

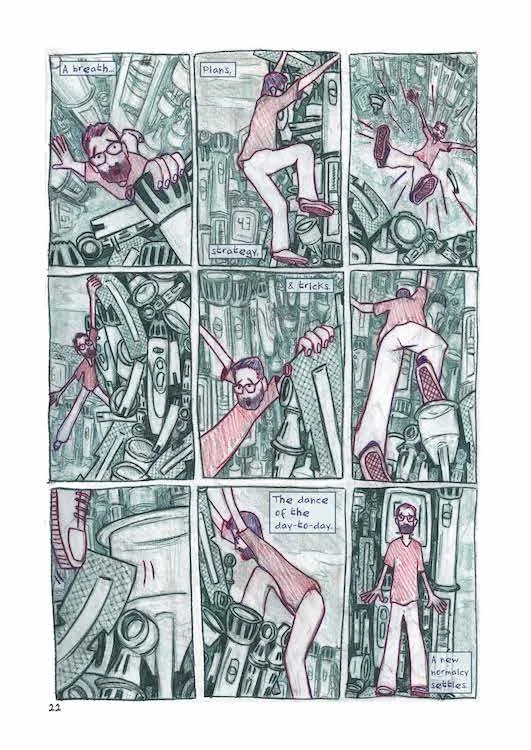

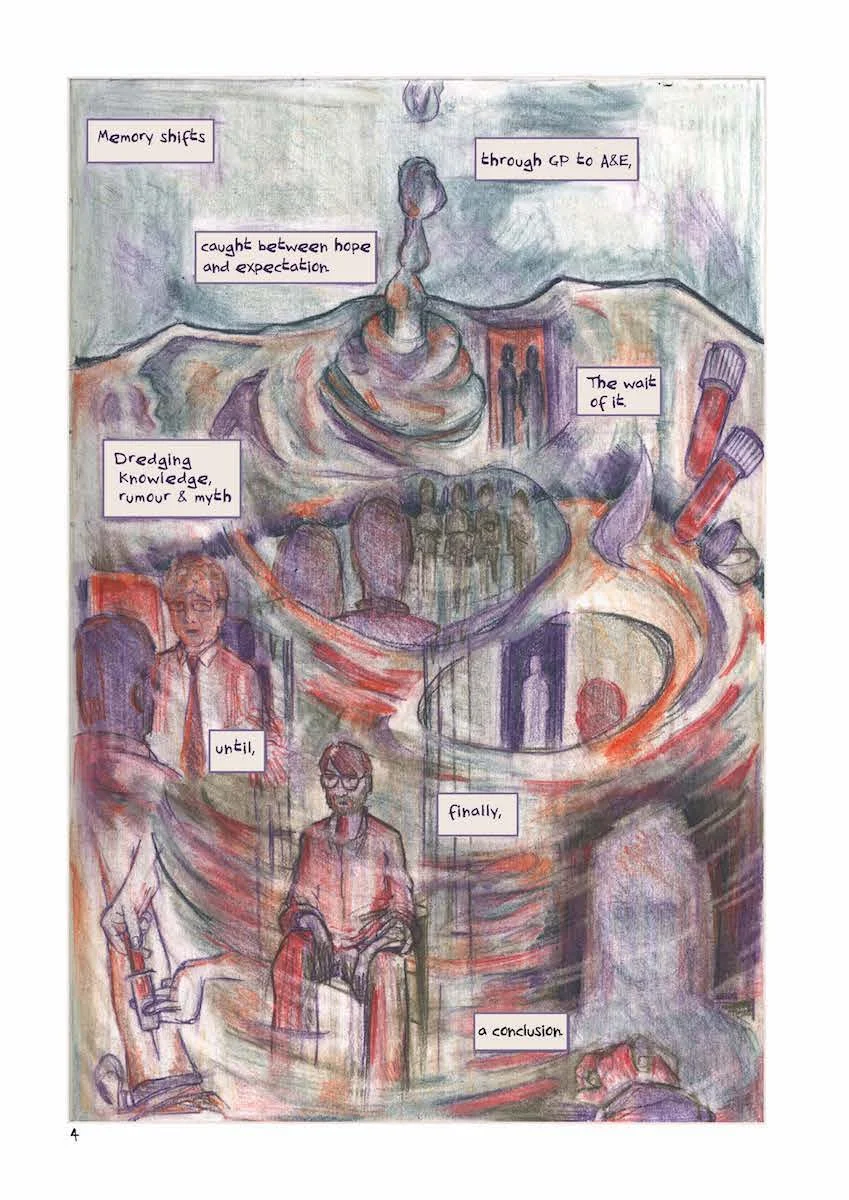

Type one Diabetes is an illness that highlights a breakdown between the self and the body – you can no longer assume the body will support your actions, and indeed you find yourself in a position of care for the working of your internal systems. In drawing Diabetes: Year One I was researching my new relationship, imagining who I am, but also reflecting on who I have become.

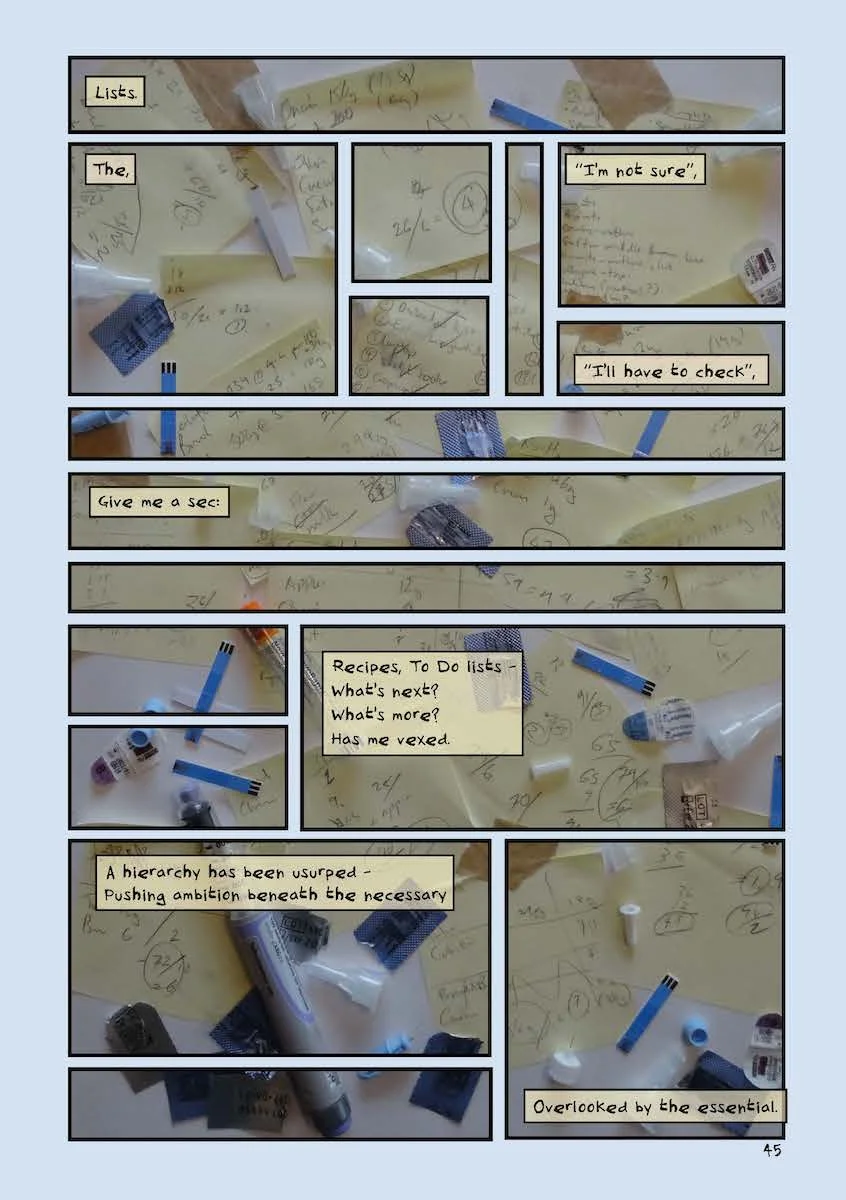

fig.1 Diabetes: Year One, page 38.

In these examples I see my body as grotesque and alien, something outside of me. The B-movie vampire [fig.1] is a response to the absurdity of having eye-drops and wearing sunglasses on a decidedly overcast day (hence the graphite colouring), and how that necessary act becomes a fashion statement and in turn a self-conscious act. The focus on eyes alludes to the potential complications of type one Diabetes (and an important layer of the comic bound up with another fear of possibly losing sight as an artist). I wonder also if the ideas of Diabetes and Vampires, is a subconscious consideration of messages that are constant about the cost of Diabetes to public-health? Whether the image is accepting, or challenging those messages I’m not sure - but I suspect, with my temperament, the latter.

fig.2 Diabetes: Year One, page 49.

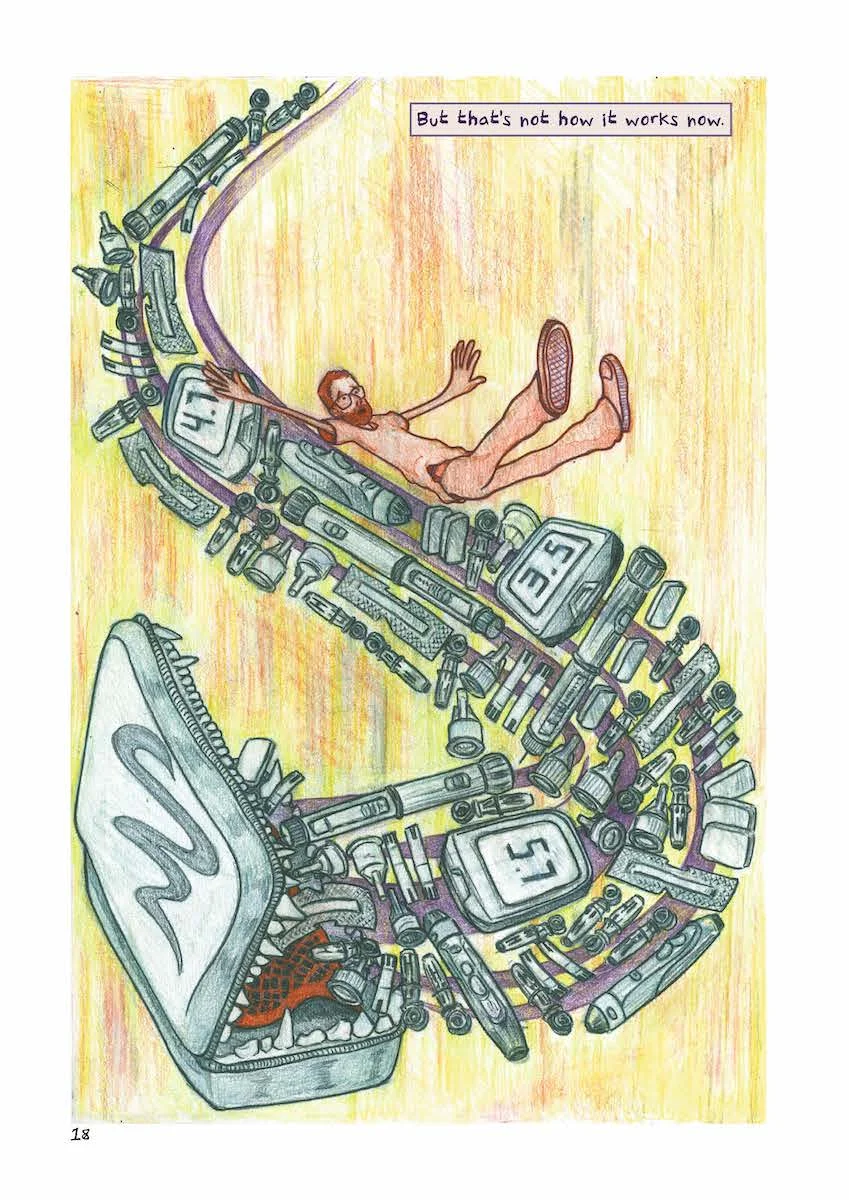

Here I draw myself as the ‘Diaborg’ [fig.2] referencing science fiction by creating a robotic armour from Diabetes equipment, but also hinting at the Tin Man from Oz in its pose. The image is both futuristic and wistful. This is a figure of internal conflict and uncertainty, a ‘self’ in flux. Coated in the trappings of diabetes, the image refers both to the day to day stuffof Diabetes, and the hopes that spring from scientific research; new ways to manage – or even in some cases attempts to cure type one Diabetes. Technological possibilities that either look to ‘build’ onto the outer shell of the body – like pumps and flash monitors; or insert new bio-engineering inside it – such as ß-cells transplanted and surrounded by a protective oxygen shield to keep out the murderous and self-destructive T-cells.

fig.1 Diabetes: Year One, page 52.

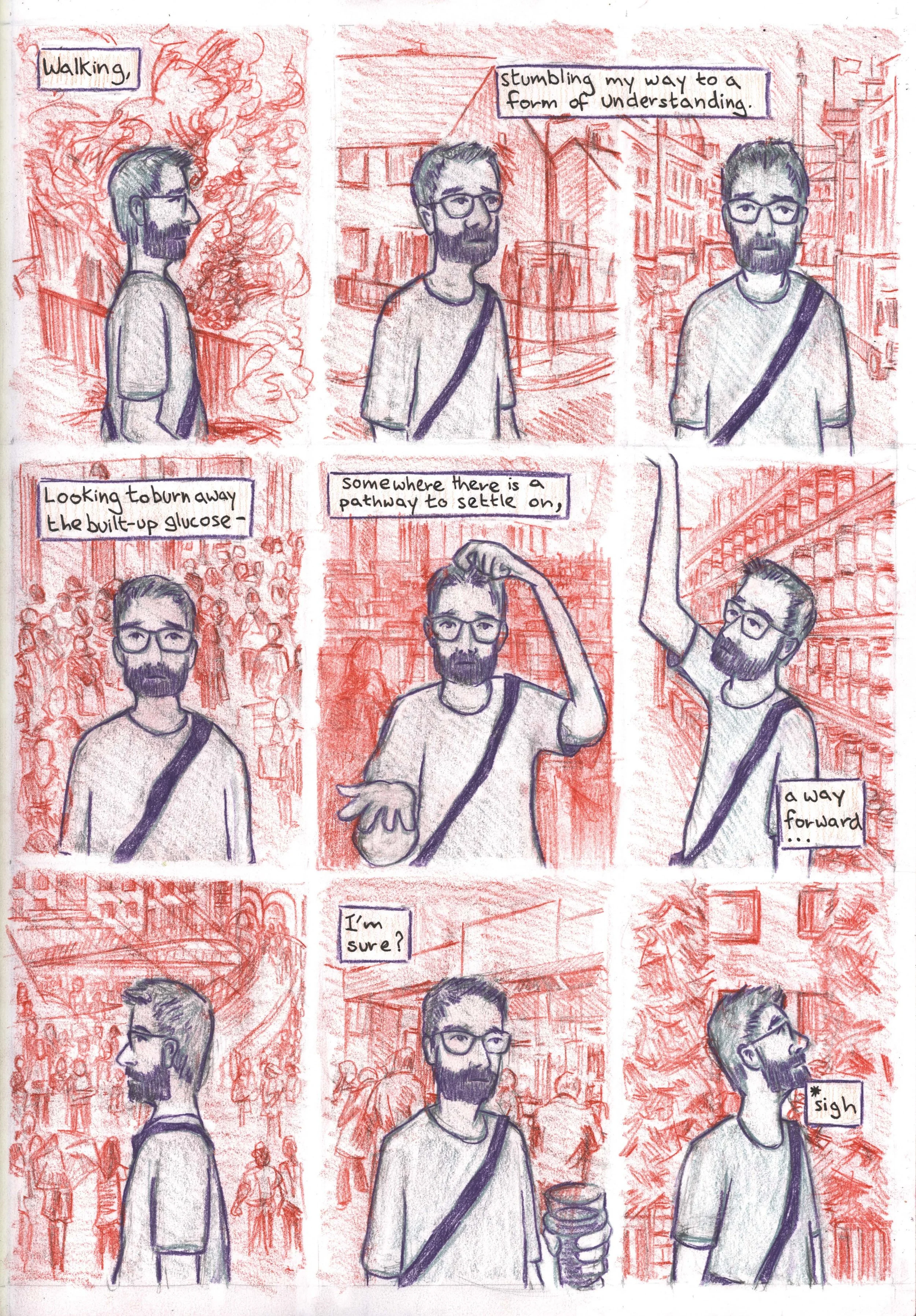

In contrast these holiday photo-snaps from the final section of the comic [fig.3] shows my body more as it is, filling out, as the insulin is able to hold the energy of carbs and sugar in my body as Glucagon. Whilst the early images attempt to imagine my new relationship with my body, these images show is my body in action, in the process of doing – they reflect on what is happening, and acknowledge success and achievement to dilute the anxiety and doubt.

Diabetes: Year One articulates and acknowledge these points of separation between the self and the body, visualising the unseen and the ways in which I come to know it. This consideration and negotiation of the outside reflects the way in which I am constantly negotiating my notions of ‘self’ between patient (diabetic) and person living with diabetes (PLWD). So, I guess I will pull on the trainers, I will strap on the belt, accept the inevitable out-of-breath-ness, and try to ignore the images of ridicule and ridiculousness that will hover at my eyes’ edge, and go for a run.

![[fig.1] Diabetes: Year One; page 4&5.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/521735b4e4b0563499dc8f68/1549272089740-QMFRU5OZX4Y8ZVWF1L5X/IMG_7248.JPG)